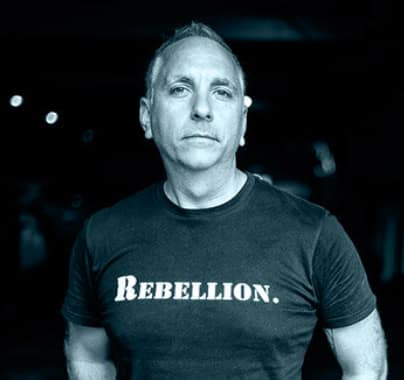

Chris Lynch, CEO and co-founder of Rebellion Defense, joins ACME General Corp. to talk about his “SWAT team of nerds” and building AI tools for national defense.

Before leading the team at Rebellion Defense, Chris was founding director at Defense Digital Service and launched programs like JEDI Cloud and Hack the Pentagon. Learn more about Chris and Rebellion Defense at rebelliondefense.com. Follow him on Twitter at @lynchseattle and find Rebellion at @RebellionDef.

ACME General: My guest today is Chris Lynch, co-founder and CEO of Rebellion Defense, which builds mission focused AI products. We’ve talked a lot about the role of AI and Defense over the past few episodes. And Chris is a vital addition to this series. In our last episode, I talked to Nick Beim about Rebellion Defense, and why as an investor, Nick believes in it. Today, we get to talk to the man in the arena. Chris, welcome to Accelerate Defense.

Chris Lynch: Thank you for having me. I appreciate you making the time and talking about this stuff.

ACME General: So Nick bragged quite a bit about your SWAT Team of Nerds, his term. Is that an apt description of Rebellion Defense?

CL: Yeah. And this is something that actually started before Rebellion. So before I started Rebellion Defense, I had a team called Defense Digital Service, which was a team of government employees that I had started at the Pentagon working for the Secretary of Defense. And we used to call ourselves the Rebel Alliance and how I described the team was a SWAT Team of Nerds. And it was this idea that let’s bring in people who are incredible software engineers, product managers, people who have built the best and biggest things on the internet, that power commerce and everything else today. Let’s bring them into the mission of Defense and Nation Security and have them more on problems of impact and things that matter.

And I think that, that became sort of not only a way to think about what Defense Digital Service was and the types of people that we wanted to have in the mission, but it even more so became this founding principle of let’s bring those types of people in, let’s breach that gap. As we’re thinking about how Rebellion is going to build products and who we want to be here on this mission alongside us became this idea of, Hey, let’s have the SWAT Team of Nerds show up and work on problems of impact.

ACME General: I have to imagine at DDS, you could not possibly have competed for talent on price. You’re paying government salaries to incredibly talented engineers who, I’m a Clevelander, so the sports fans will get this could take their talents to Miami, right? They could go anywhere they wanted to. How did you draw the best and brightest into the Pentagon?

CL: It’s interesting. I get this question a lot. I got it at DDS. I get it today at Rebellion and you’re right, I think that if you want to set out with this idea that we’re going to be able to competitively build out technical talent in the government, at the Pentagon on price and how we can pay people, I think that that’s an impossible target. We will never be able to hit success as a government. Of course, doing a startup like Rebellion, you have more flexibility because you have equity and you have a variety of different tools that you can use to attract talent. But I think that the core principle of how we were able to be successful in bringing those people into Defense Digital Service in the Pentagon as government employees still applies.

I think that the Department of Defense and our allies and partners have one of the most important and incredible missions in the entire world, they actually work on things that are of consequence. And I think that most people, myself included, I spent a huge portion of my life working on technology or products that I thought were interesting or novel or unique. But as I look back now, I think those things are ultimately meaningless. And I think that what we have to do is make it seem like there’s a place for us. We have to create that place where people like me can show up in this world of Defense and have an impact because the mission does matter.

So I think that what I would focus on is this idea of, come here, work on something that is so profound, you’re going to have an impact on people’s lives. People who will never know your name, they will never know what you did, but you will fundamentally change something so important for them that it will go with you until the day you died, that you did something that mattered. And I think that we have to focus on that because that’s what we provide. That is what the mission of Defense is. It’s something that’s bigger than me. It’s something that is bigger than even the team that I’m on. It’s bigger than the technology. It’s something where I can have an incredible impact and change people’s lives. And you know what? Some days it’s going to be miserable, some days it’s going to be so hard and so terrible.

And you’re just going to wonder to yourself, “Did I do the right thing by coming here?” But then you’re going to have that moment. You’re going to hit this peak where you’re like, “Holy shit, what I just did actually mattered.” And you’re going to say, “Okay, I did that. And it was all worth it.” And I think that that’s… What’s so important is that we missed the opportunity to actually create the place for people who are technologists and software engineers to come into Defense and Nation Security. I think we miss that a lot. And I think we also miss the opportunity to talk about the impact they can have and why it matters, but also acknowledge that it’s going to be really frustrating and very hard sometimes.

ACME General: How did you, Chris Lynch, become such a vocal evangelist for this mission. You’re not a vet in your previous career. What brought you to it?

CL: I would actually say that I went through the majority of my life without any interaction with either government or military in any way. I would watch movies, I would see TV shows, and that was pretty much how I had any exposure to the military. I spent most of my life, either building software, running software engineering teams, doing software startups, but nothing around government or military. And I had this strange and unexpected moment in my life where a friend of mine had been called to duty to try to turn around a thing called healthcare.gov, which if you remember that, was a website and a set of services that the government launched that on the day that it launched after spending, I think, someplace almost close to a billion dollars, it launched perfectly, everything went so well. Everything was great, except that it was, I think, only six people could create accounts on the day that it launched.

Now as a technologist, you might look at that and say, “Hey, that seems like a lot of money was spent on something that didn’t really work.” And you would be right. I had a friend who got called to go in and help turn that around. And that person connected me with the White House who was at that moment, forming the aftermath of that, which was called United States Digital Service. This idea of, let’s bring people into the government that can help on sort of these problems that are facing the citizens of our country. And I originally went out for 45 days because I was so convinced that there was no ability for me to have an impact on anything that was going to happen.

And in a way I picked the 45 days because it seemed long enough that if I showed up for 45 days, I would be able to prove myself right. And my bias that there was no way that a person like me would have any place to make an impact out in the government. And I worked on veteran medical records, transfer from the DOD to the Department of Veteran Affairs. And what we found is that ultimately veterans were running into a thing where they would have incomplete medical records that could ultimately result in some fairly terrible outcomes when they tried to receive the benefits and the care that they deserved from their service to our country.

And what we found is that it was mostly down to how medical records have been scanned and digitized out in the field. Now, if you think about it, you got these doctors who are out in some really difficult places and they’re scanning medical records, and they don’t know if a PDF or a TIF or a JPEG or the right formats for what they’re scanning. Yet they had that opportunity to select, but it turns out that if they scanned any medical record is anything other than a PDF, they would actually never go to the VA. And when a veteran was looking to receive care or treatment, they would find out that those medical records were missing. They would go through this adjudication process that I kid you not, could take up to seven years.

And if you need chemotherapy or other types of treatment, that might actually end up being fatal and it’s heartbreaking. And what we did is wrote file format converters. If you think about it, so mundane. File format converters, and then all of a sudden somebody’s life is so profoundly changed. And I had never worked on anything like that. This thing that started as a 45 day unexpected detour in my life became a complete rerouting that would result in me founding Defense Digital Service, originally working with secretary Ash Carter at the Department of Defense, and then continuing on with secretary Jim Mattis and working on some of the biggest problems that we were facing in the department. And that would fundamentally change my life.

I’ve been here in the Washington, DC area ever since. I’m seven years in and founding Rebellion Defense here is a good example of just how I think things like this change, not only your perspective, but they help you understand what the word mission means, and they help you feel like you’re part of something that is, I don’t know how to say it any differently, something that is just bigger than you and matters. And I think about it a lot, even on the days when it’s really frustrating and hard.

ACME General: I’m sure there are a few of those days working with DOD. You are at Rebellion, a Defense first company that’s explicit, which makes you pretty unusual among tech companies. And I know that’s partly a business proposition, but it’s clear that it is also a moral one. How does your team respond to that moral imperative? You’ve, obviously, got a bottom line. You have to make money, but it sounds like there’s a lot more to it in terms of the culture at Rebellion Defense.

CL: There is. I ask myself a lot. Why is it that some of the best and brightest software engineers go and work on anything other than Defense and Nation Security? Why is it that some of those engineers, as they’re going through a computer science program at a university, why is it that they might work on Defense research projects while they’re in the university, but then ultimately end up working on anything but Defense? Why does venture capital fund primarily companies that are called dual-purpose, but not those that are focused on Defense and Nation Security exclusively? And then maybe lastly, why do we believe as a nation that those people, the people who serve our country should not have access to the greatest, most impactful technology to not only keep them safe in what they’re doing, but make an impact and keep us all safe. Why should they not have the best technology?

These are big, fundamental core beliefs that began the idea of creating Rebellion Defense. What would it mean to create something a little bit different? We began with this idea of let’s create the next generation software company focused on Defense and Nation Security. Let’s become exclusive. Let’s become that thing that is exclusively focused on that mission and that need, and that output. And I keep saying the word mission, because I think it’s really important.

I was at our Seattle office last week and I was walking one of our seed investors through the office. And I love to go through and introduce people to our rebels. And one of the things I always ask and I started this at Defense Digital Service is to say, who are you? And what do you do here?

I was walking through and I was introducing rebel after rebel to this early seed stage investor. And then we were having lunch afterwards and he made this comment to me that I thought was pretty cool. He said, “I noticed that every single person said the word mission. And I was just curious how you think about that and how that became so important.” And I think it’s because as technologists, we want to work on hard problems. We want to work on things that actually matter, but I sort of feel that we’ve been locked into a world where we’ve got to work on selling ads or we have to work on, well, selling ads with cool filters on videos. And it’s interesting, but I don’t know that it matters.

We wanted to start a company that would change that and create that space, would have the mission there. And we wanted to build products that were ultimately going to do a couple things. If you think about the history of Defense, and if I were to walk out on the street and I were to run into a random person and say, “What’s the first thing that you imagine when I say, the army or the Navy or the air force or the Department of Defense?” The answers will likely range from a soldier on the ground to an aircraft carrier, or a jet, or a satellite floating around an outer space.

And we think of this industrial vision of what Defense is and rightfully so, because that has been how advantage has defined the Department of Defense have been our industrial manufacturing might. But there’s this really weird thing that has been happening. As Silicon Valley became, and I’m not talking about a place, but as this, this concept of Silicon Valley, this concept of the innovation that drives so much of how we live our lives on a day-to-day basis and what we do. When you think of that, this thing called Silicon Valley sort of grew up. And while there may be so many things that came from research and partnerships with Defense and Nation Security, it has over time become its own thing and it grew apart and grew away.

When you think about Rebellion and what we want to do, we want to build a place where we can actually create products that are focused exclusively on the mission of Defense and Nation Security. We can build things to create advantage for the upcoming era of Defense, the software era of Defense. And in the way that we think of industrial manufacturing might as being the key defining characteristic of where we were, we have to think about how the world of the future will be changed. And I think you’re seeing that even play out right now. Russia invading Ukraine is a good example of how commercial technology has completely reshaped how we see, understand, and also how operations are going to be executed even within the military themselves.

Let’s create that thing. And Rebellion is built around this idea of the software era of Defense. One that is going to rely upon the flawless execution of software that is going to define the key characteristics and the advantages that are going to unite and drive forward even the hardware platforms and the industrial things that we think of that are so important to actually how conflict might play out.

ACME General: You have built this unicorn and attracted a pool of incredibly talented engineers and built a culture that in many ways defies or goes against the conventional wisdom against the stream. And just a few months ago, some of the industry lit about Rebellion Defense that I have poured over was talking about whether you’d be able to motivate that talent, given the challenges that places like Google and Microsoft have faced over employee unrest with military related work.

I am wondering though, if in just the past few months you have seen a tonal shift, a cultural shift in this ecosystem, given that we can no longer hide our head in the sand and pretend we don’t need a robust National Defense. The world, after all, is a dangerous place. And those who would’ve denied it a year ago have to confront that now. Has that affected conversations in your orbit?

CL: It’s maybe as I think about it, it has made the discussion and the point that you just made more acute. I spend a lot of time talking to people through this conflict. I’ll say it’s the internal conflict that people might have of, “Hey, do I go to this company and work on video filters or ads or work on commerce or whatever it is, or do I do something different, something that maybe I’d never really thought about? And this is this idea of Defense and Nation Security, do I do that?” And the invasion of Ukraine emphasizes to me a point that we’ve been making for a very long time. We don’t get to define if conflict is going to occur or not.

Russia decided to invade the Ukraine and their invasion of Ukraine is something that we’re all watching now. And we have to react to and respond to. It is also heightened in my mind, this threat that we’ve known exists, which are authoritarian regimes aren’t waiting around to see what we think they should do, and we can’t control that. So I think that there’s actually an easy way to go through this for the… If you’re sitting on the sidelines and you’re wondering, how do I participate? Should I participate? Should I do something that I never would’ve considered? Should I do what Chris did in 2015 in coming and working in either the government or join a company like mine at Rebellion? Should I do that?

Here’s the thing. Go create the world that you want to be a part of, go build the things that you think are important. Go create the technologies in the way that you believe that they should be used. Don’t sit on the sidelines and ask yourself, “Should we be using artificial intelligence, machine learning and computer vision in Defense?” That is a waste of time. Instead, go build it. As we believe that it should be used in a nation of laws, in a nation that is ultimately here to help defend and protect those who serve and our allies and our partners alongside us, go create that place. Go be a part of it.

Think about how you want to build those technologies. Think about how they should be used. Go build that world. You are actually a key part of it, but don’t sit on the sidelines and ask questions and imply that we have some kind of narrative that we get to define for other governments and other parts of the world. We don’t get to do that because we don’t get to what they’re going to do. And there have been pieces of this over time, right? Right now, Russia invading Ukraine, there’s a potential that it could escalate in ways that nobody imagines right now. But we’ve also seen North Korea launching test platforms and ICBMs, right? These things are happening. We’re watching China build man-made constructed islands in the South China Sea and putting jets on runways on those. That’s not something that we can just ignore.

And we also should use everything in the world that we can to prevent conflict. But I think that we just watch that with Russia. Sometimes we just don’t get to control that. What are you going to do about it? And I think that the answer is build the place that you want to be, build the future that you want, define how these technologies are going to be used, because if you expect that everybody else is going to simply do it the way that you would want, I think that you’ll be pretty disappointed by that. No one else is coming. Come build that place.

ACME General: I have heard you say again and again, that the engineers, the technologists who believe strongly in these things need to show up and I’m going to quote you here. You said, “if other countries who do not share your beliefs, become leaders in these capabilities and how they are used in a military context, it doesn’t matter what you think. That has now become the norm. And we’re seeing that unfold right now.”

CL: Yeah, it is scary. It is depressing. But I think that you can wake up in the morning and either be wandering through the forest of what that feels like, or you can do something about it. And maybe this is just me, but I think you do something about it. I think that it’s a lot less scary to feel like you are creating a place that is hopefully safer because we had information advantage or the ability to understand what our adversaries might be doing. I think it’s a easier place for me to imagine that we provide our military and our allies and our partners, and as a nation of laws that we have the ability to maintain decision advantage.

And not that anybody wants conflict, it’s not that at all. But I want to know that if we are in a place where it is unavoidable, that we provide our military, the people who showed up in this mission, by the way, is a volunteer fighting force here in the United States, that we have provided them with every advantage that we possibly can. And we have provided them with the technology that is not only going to provide that advantage, but is going to be coded with the ethical and the moral beliefs of this country and how we look at how conflict must unfortunately be done. And that’s a pretty powerful place to be. It’s better than just feeling like you’re caught in the undulating waves of the ocean as a part of it.

ACME General: That’s a powerful call to action, and you’ve been able to make good on it at Rebellion Defense. But the reality is that the Defense procurement system, as it exists today is barely compatible with the way Silicon Valley works. And with the way startups think and are funded. I’ve heard you say that traditional startups just can’t function in this space and you had to build something from scratch to exist as a Defense first company. How do you fix that? How do we scale culturally what Rebellion Defense has done so successfully?

CL: A few things come to mind. I’ve spent a lot of time so far talking through this idea of showing up. So that’s one, you mentioned, what does Silicon Valley need to do? I think that they need to show up. That’s not only the people, by the way, that’s also money. The reality is that most venture firms are not a believer that they can build a business in this space. And I think that that’s uninformed, unfortunate, and sad, and wrong. So we need funding to go to companies that are going to play in this space. And I don’t think that we need venture firms to talk out of both sides of their mouth and say, “Hey, I’m putting money into dual-purpose companies.” That’s not what I’m talking about. We want to fuel and fund the ability to have that advantage that I was talking about before.

So we need Silicon Valley, not only to show up as software engineers, product managers, designers, but we also need Silicon Valley to show up with checks and fund these companies. And I would challenge anybody in the venture space today that if you are not writing checks to companies to go build the next generation of software companies and startups focused in Defense and Nation Security, I think you are missing out on what is an amazing and incredible mission in a market that is very important and meaningful and a place where we can build enduring important companies. So that’s one.

You brought up acquisition and Defense. Here’s what I think, I have a slightly different view on this after being in this space for about seven years now. Coming from the inside at Defense Digital Service, working on a very difficult acquisition around commercial cloud called JEDI, Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure and making an impact in a variety of ways. And then ultimately, going and starting Rebellion along with my two co-founders Nicole Camarillo and Oliver Lewis.

Here’s how I think about the acquisition side of this, the acquisition side’s not perfect, and it is deeply biased towards the Defense industry and all call the Defense industry. The industrial manufacturing companies that we think of that were mostly started around or before World War II in some form, or the services and integration industry that has popped up in the last 20, 30 years around it. It is deeply biased towards those companies. So I think that founders and investors need to ask themselves, what are they building and what does that look like? And what might some outcomes be?

And there are numerous companies that actually have no expertise in this space that have gone and partnered with integrators or some of the Defense industrial based companies. And they work with them and they provide software and technology without having to learn how to sell into this space. And they find a way to impact the mission. I actually think that, that is a perfectly fine way to build a business. And that is a thing that I think is the easiest entry into this market. A, bypass most of the acquisition problems, but most importantly, B, you end up being able to have an impact on the mission and what’s happening.

The other type of company that you can build is probably more akin to Rebellion in a few others that I think everybody is focused on right now, which we’ll say is, these new wave of Defense unicorns. And those companies are funded against what I’ll call the long game. It is true. There are things that you have to do here. There are taxes, and I don’t mean taxes like we pay. There are business taxes that you have to deal with in order to build a company in this space that is trying to make a much bigger impact. It is 100% true. You have to fund it differently. It’s a long game. You have to have patient investors. You have to have more capital than you would at a normal startup. Why? Because it takes longer. There are just parts of this that are not working on the same cycles that startups work through.

All the traditional advice in wisdom that we think of it’ll come from almost anything that you read on the internet or from tech accelerators and things like that, you’ll say move fast. Well, some things just don’t move as fast. The budgeting process, as an example in the government, is an annual thing. It is an annual thing, and it’s actually planned even longer than that. But Congress comes and they create a budget, that takes time. We would like for them to move faster. Sure. Is that a fair expectation? Maybe over time. But right now, I think you got to plan against it. I think you have to fund against it. I think you have to have patience against it. And I think that you have to have intestinal fortitude to actually say, “Hey, we’re tracking in the right direction. We’re just not going to do all these things that you may be looking at in traditional portfolio companies and here’s why, and here’s where it goes. And here’s these things develop.”

And by the way, I have to spend a tremendous amount of my time describing to investors, how all of that works going from budget cycles to programs of record and, research and engineering, or research and development and different types of colors of money and all this stuff that makes no sense to anybody else. And we have to educate that. I actually think that the department should spend every moment instead of going out and doing dinners with venture capitalists and talking about how they think that investors should be investing in different types of technologies, they should send a ton of time going out, and instead, informing those investors on how completely strange and unusual that whole process is because I spend a ton of time doing that myself and I’d like a little help.

So that’s one thing that I would like to see. Now, here’s the other part, could the acquisition system be better? Could there be more authorities? Sure. But the reality is that there are a lot of authorities. And I think that this comes down to another piece, which is human capital. One of the great things about Defense Digital service and that founding, and this idea of a SWAT Team of Nerds was bringing in technical people to bridge and partner with those who know the mission. See, I am not brave enough or courageous enough to have served in our nation’s military to go on missions with them. I can be a partner to help them be successful. That’s an incredible opportunity.

It actually also does something else that is very important. It helps our military and our civil servants understand where technology fits, how to think about it, not be fooled by what might work or isn’t actually the art of the possible for where we are today. I think that part of the acquisition conundrum is that we have to do a better job of establishing what it means to do software acquisition, buying software, not buying a big, heavy jet sitting on a runway or on an aircraft carrier, but software, which is going to define the advantage and the characteristics that tie all those things together, especially against technologically advanced adversaries. And we want to up level those people. We want to be a partner to them, and we have to have incredibly talented technical people by their side in order to help them do that. So I think that that’s the third bit.

And then I think that you just have to have people who aren’t afraid of moving fast with smaller failures, but are instead trained to live with very slow, very long failures that everybody watches on PowerPoint charts and Gantt charts. I would rather fail very, very fast, very quickly and redirect. And there are methods to do that. You don’t have to do DOD 5,000 for every acquisition. We have mechanisms to do this that allow us to learn new requirements, that allow us to change requirements, that allow us to quickly address failures instead of watching a train wreck in slow motion and being like, “Shit, if we’d only known that.” Well, we did know that five years ago, right? That’s the type of stuff we want to do.

So I think that a lot of that is actually there. I think that we just got to do a better job of establishing, what do we want to be? We want to be very good at acquiring software. We want to become very good at trying smaller bets that can scale and grow over time. And I’m not talking about servers by the way. I’m talking about smaller bets that are going to have a direct path that people understand how it is going to actually become important. And we have to do that. So that’s an important thing. And we are finding those places. They do exist. There’s just an opportunity for them to be more of them. And then we need people to show up into the mission and help educate and inform as to what success looks like.

ACME General: It sounds like some serious disruption is called for. And you have been that disruptor in several contexts. I’m wondering, is it easier inside the system like you were at Defense Digital Service or is it easier to be a disruptor from the outside pushing in?

CL: It is, they both have their challenges and I’ll go back to something I said earlier, the peaks and valleys are far and wide and tall and deep, no matter if you’re on the inside or if you’re on the outside and you know what? It’s hard enough to create a startup, to create a business, to go from zero to one. It’s hard enough. But I think that because it’s so important, it does make it all worth it. As far as where you can have the most impact, they’re just so different, but I’m in a fortunate place where I got to work on how we change and disrupt, and reshape many things from the inside. And I’m deeply proud of that service and the things that we did.

But it informed something in me that I suppose led to Rebellion. And many of the ways that I think about how we view disruption from the outside and having the courage to be a part of it. And that is that you can still advise and be a good partner from the outside. And I think that that’s the thing, we have to view it as being a good partner. And I think that if we do that, we have an opportunity to really change what the department is doing and they want to learn, they want to be a partner, they want to hear our thoughts as to how they do this. Funny enough, I’m not sure which one I could say is better or worse. They’re very, very different. But I do think that I learned so much on the inside that has given me both empathy, but also just keeps me angry enough that from the outside, that I can be like, “No, no, no, no, no, we can’t do that and here’s why, and here’s what we have learned and here’s how we have seen it.”

And I think that, that fuels me so much, to be quite honest. It fuels me so much on any given day to be able to not only provide some of those anecdotes or outcomes, or results, but still wake up with the belief and the hope, and the spirit that I know that we’re going to be heading down the right path. And I do. I actually, I’m very optimistic that we’re heading down the right path. We’re standing on the shoulders of giants of many different things that have gotten us to this point. There’s still far more to be done. And that piece right there is what fuels me so much.

ACME General: You’re a Star Wars fan, Chris, to put it mildly. And you refer often to the Rebel Alliance, you call your engineers your rebels. If they’re part of the Rebel Alliance, who’s the empire?

CL: Where we are coming from and what has made us successful and where we need to go are fundamentally different things. And I think that the Rebel Alliance, which I’ll call this loosely connected group of people, both from the inside and the outside who are united in this belief that we can build a better future that is going to provide information, decision advantage, better use technology, change these things, that Rebel Alliance, I think that you want to be a part of that thing. And I think we need to let everything else go. I think that we need to find the coalition of the willing.

There’s nothing that’s more disappointing to me than the individual who thinks that how we do it is good enough. There’s nothing more disappointing to me than the individual who says that the software and the technology that our war fighters are using doesn’t need to be as good as, or doesn’t deserve to be as good as what they use every day when they go home in their personal lives. I think that we have ended up in a very sad place with that belief. And there are those who hold that belief that it’s good enough for government or good enough for Defense.

If you believe that something just needs to be good enough, shame on you. This idea, this concept, this hope of the Rebel Alliance is one built around a belief that we deserve more, better, and that we believe that we can change where we’re headed and that it is not a written place that software and technology must be good enough. It is not a place where we believe that we don’t get to actually build the systems that can use technologies that are going to be so important. And we can actually make them things that we are proud of, things that we trust.

And I think that the other side of that is not something that I want to be a part of. And nobody thinks that they’re part of that, by the way. I met a lot of people who would show up and say, “Hey, I’m part of the Rebel Alliance.” But I actually put it down to one thing, let’s have the courage to try. Let’s have the courage to do something that feels a little uncomfortable. Let’s have the courage to try something that actually might fail, but make it small enough that we can still recover and move forward. And I’m not talking about putting people at risk. I’m not talking about making rash decisions. That’s not it at all. That’s unfair, if that’s where your mind went. I’m talking about, let’s do something that takes enormous courage. And if we are successful, we might just create that future.

ACME General: Well, Chris, this has been fantastic. I really enjoyed the conversation. Thank you so much.

CL: Thank you for having me.

Find us in your favorite podcast app.

Find us in your favorite podcast app.